In a very interesting piece written for BBC Travel, journalist Kathleen Rellihan touches on the effects of tourism and asks herself if it is now time to rethink the meaning of ‘being a tourist'. I can relate to so much of what is written in the article that I felt the urge to write this post.

For Kathleen Rellihan, it all started in the sweltering heat of a June night in Rome. And I have recently had a very similar episode myself in Barcelona, navigating a sea of tourists at every landmark. “There are so many tourists here” is something I grumbled more than a few times during my travels over the past decade or so.

And I know what you are thinking: “you are a visitor yourself”. That is true, but I always felt that my approach and behaviour were different.

Nearly twenty years ago, Anthony Bourdain premiered his TV show No Reservations with the mantra “Be a traveller, not a tourist”. Like many other globetrotters, I've long clung to this “traveller” identity. I always take a considerate approach to experiencing a destination.

A “tourist”, on the other hand, is stereotypically cast in an unflattering light: unadventurous, prone to herd mentality, perpetually vexing to locals (and other visitors) as they angle for the perfect selfie.

However, in the wake of the post-pandemic travel resurgence, the negative effects of tourism have reached alarming new heights.

Why Does It Feel Worse Now?

There had been a sort of silver lining with the lockdowns, and a world closed to foreign visitors. Residents have had the opportunity to see their cities with nobody else around. It was eerie for the most part (see my empty London, for example), undoubtedly, but also not entirely unpleasant, if you see what I mean.

When things returned to ‘normality', everybody needed to travel elsewhere ASAP. Disrupting the forced ‘peace' of the cities like a river breaking the banks after a week of torrential rain.

Tourism had been forgotten for two years, but mass tourism's problematic effects resurfaced very rapidly. The term “tourist” has again become synonymous with the destruction of cities' character, the displacement of residents, the degradation of natural wonders and ancient ruins… Even the acceleration of our planet's fragile climate.

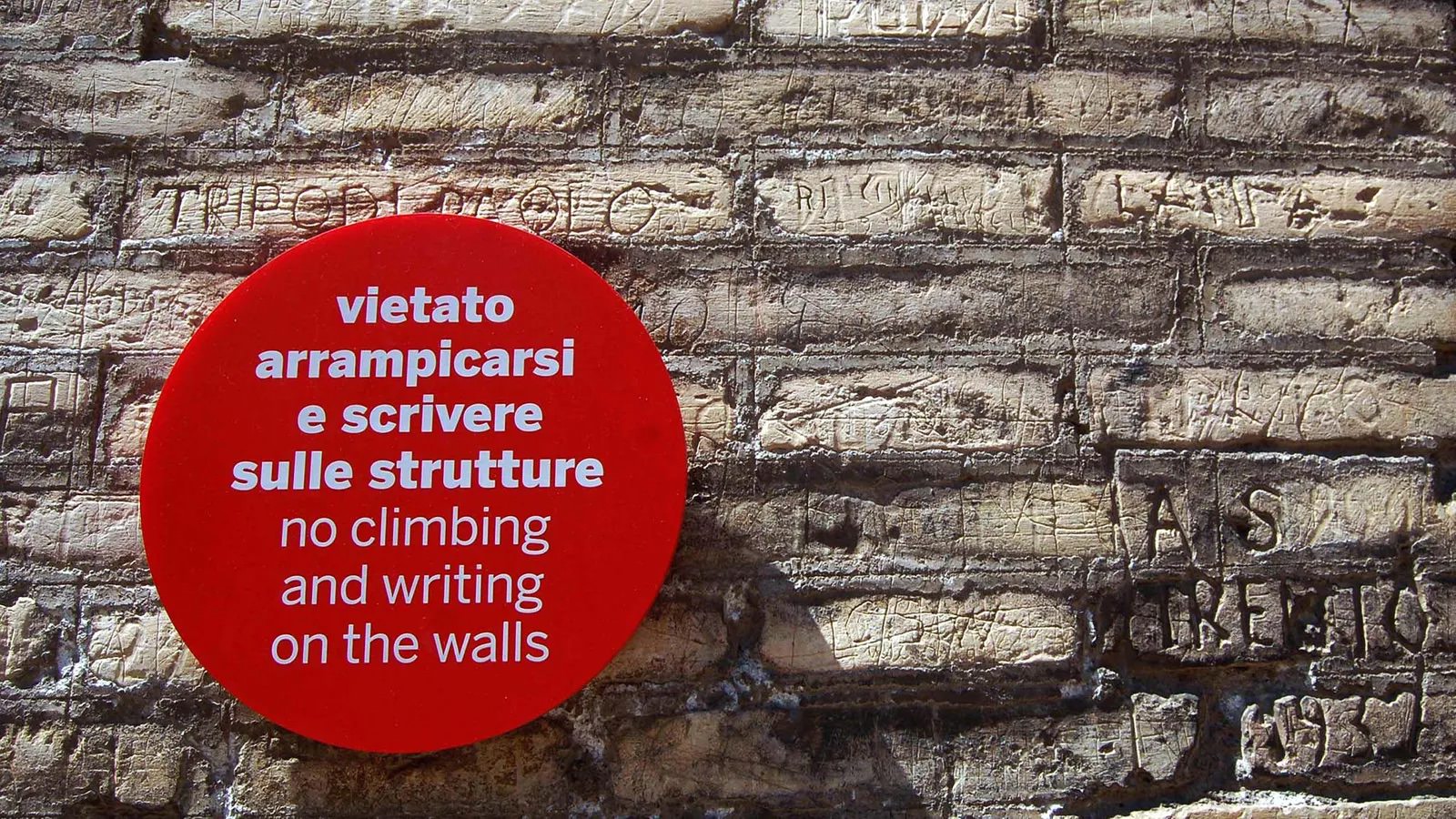

Not to mention all the recent mentions of “tourists behaving badly” that dominate headlines worldwide. In my hometown Florence alone, within a month, tourists have damaged the Fountain of Neptune by climbing it and defaced the Uffizi Gallery by spray-painting football slogans. And the beautiful city centre is now totally surrendered to tourists. But episodes like these are seen everywhere.

And in Barcelona, the locals have had enough. Last year alone, there were 30 million visitors (in a city of 1.6 million residents). Gosh.

The Double-Edged Sword of Tourism

It took Kathleen Rellihan delving into Paige McClanahan's thought-provoking new book, “The New Tourist: Waking Up to the Power and Perils of Travel”, to confront an uncomfortable truth: she is a tourist. And I may be one myself, quite possibly. But while that label carries weighty implications, it doesn't have to be an inherently negative one.

An American journalist based in France, McClanahan meticulously chronicles the ever-shifting power dynamics of travel and its capacity to transform destinations across the globe—for better and for worse.

She highlights how tourism can serve as a lifeline, pulling countries back from the brink of economic ruin, as seen in Iceland. Yet, unchecked tourism can also ravage the very allure that drew visitors in the first place, overburdening natural environments and local communities.

“Does tourism build up our world? Or does it tear it apart? The only answer to both of these questions is ‘Yes'”, McClanahan asserts in her book. This paradox demands our attention, especially as we enter another high-stakes travel season.

In an insightful interview, Rellihan and McClanahan shed light on the critical effects of tourism the book tackles. From the climate crisis to over-tourism to the pervasive influence of social media. The author underscored the urgent need for a collective shift in how we perceive tourism and our roles as tourists.

Embracing the “Tourist” Label

McClanahan argues that many harbour an aversion to being labelled as tourists, associating the term with close-mindedness and clichéd, mass-market experiences. However, she reminds us that whenever we venture away from home, we are all, in essence, tourists. Accepting this label, she posits, is crucial for fostering self-reflection and accountability. We created the tourist/traveller dichotomy to feel better about ourselves and side with ‘the good ones', but the difference may not exist at all.

By othering tourists, we distance ourselves from the problems they are accused of perpetuating. “It's way too easy to point the finger at those people ‘over there' who are causing the problems that we read about in the headlines”, McClanahan explains. “Whereas if we actually incorporate this identity of the tourist, to some extent, into our own identities, then we implicate ourselves, right?”

McClanahan asserts that embracing our roles as tourists empowers us to become agents of change within the tourism industry. Rather than looking down on tourism, we must elevate our expectations of what it means to be a tourist.

In doing so, we can shape tourism's impact on the world. “Be the change you want to see in the world” (a quote mistakenly credited to Mahatma Gandhi).

The Responsibility of Last-Chance Tourism

McClanahan grapples with the complex phenomenon of last-chance tourism. It's the idea of flocking to destinations threatened by climate change “before it's too late”. Such as the rapidly receding Mer de Glace glacier in the French Alps, or Jökulsárlón in Iceland.

While the irony of ramping up carbon emissions to witness the consequences of those very emissions is not lost, McClanahan suggests there is an opportunity to imbue these experiences with greater meaning.

She points to emerging research indicating that, under the right conditions, visiting a disappearing glacier can inspire individuals to adopt more environmentally conscious behaviours in their daily lives.

The key, McClanahan emphasizes, lies in the approach.

“The way to maximise the chance that you're going to have an impact on the visitor's perspective and ultimately their behaviour is if there's two things happening: education, and an emotional connection of feeling implicated”, she explains.

Tourism operators bear a significant responsibility to craft experiences that promote education and foster an emotional bond with the land. As tourists, it falls upon us to educate ourselves and immerse ourselves in these environments rather than simply seeking a fleeting photo op.

It's also the foundation of many photographic projects, including some I'm planning to do myself soon: visit (but leave no trace), testify, and inspire change.

Navigating the Influence of Social Media

McClanahan addresses other multifaceted effects of tourism, such as social media's impact on travel. On one hand, platforms like Instagram have democratised travel storytelling, amplifying diverse voices and perspectives. “We all have the power to tell our own stories”, she notes, contrasting this with the historically privileged domain of wealthy white male travel writers.

However, with this power comes the responsibility to wield it thoughtfully. Whether we have a modest or substantial following, McClanahan argues that we are all accountable for the narratives we share about the places we visit. “Are you depicting an honest representation of the reality as you experienced?” she prompts. “Are you sharing nuanced content that's helping your viewers or readers or followers gain a greater depth of understanding about the place?”

As content creators and consumers alike, we must approach social media with intentionality. Striving to paint authentic, multidimensional portraits of the destinations we encounter. And always be respectful of the places we visit, considering the impact we have while there and the impact of what we share.

By the way, I don't restrict the definition of place to the location: we should all be respectful of cultures, laws, individuals… When I visited Istanbul for my travel photobook, it was Ramadan, so an even more sensible time. But I saw tourists misbehaving in every possible way for the chance of a selfie. It was appalling.

The Shared Culpability of Overtourism

When faced with the ramifications of overtourism, it's tempting to lay the blame squarely at the feet of tourists. However, McClanahan argues that the issue demands a more nuanced examination.

“It's really easy to blame tourists. ‘Oh, my God, all of these tourists', because they aren't us. When we talk about tourists, it's always them”, she points out. Yet, by othering tourists, we absolve ourselves of responsibility. But locals have their share of blame too. OK, maybe not you, John Doe and me specifically, but local authorities who have the power to decide how to tackle problems.

McClanahan asserts that while individual tourist behaviour certainly plays a role, governments and city officials also bear a significant portion of the blame. She cites the examples of Barcelona and Amsterdam, cities that aggressively courted tourism, only to later grapple with the fallout of their own successful marketing campaigns. Amsterdam's Stay Away campaign is a particularly telling example.

“Governments have accountability here—the city leaders always need to remember who elected them and prioritise the needs of their residents”, McClanahan stresses. At the same time, she acknowledges that as tourists, we have a duty to educate ourselves and make informed decisions when exercising the immense privilege of travel.

Sometimes, it's not even a tourist problem. Particularly after moving to the UK, I have had more than a tolerable number of sleepless nights because of my neighbour's behaviour. And we can't really forget what the locals can do here during sports events… No, it's not celebrating.

The Case for Tourism in a Fractured World

Despite the litany of challenges attributed to the damning effects of tourism, McClanahan remains a staunch advocate for the transformative power of travel, particularly in the face of the existential threats looming on the horizon.

“If we think about the challenges that our species will face in the years and decades to come—the big ones like catastrophic climate change, possibly a pandemic even worse than Covid, global thermonuclear war, runaway AI—every single one of these crises is completely blind to the idea of a national border, like Covid was”, she reflects.

In an increasingly interconnected world, the ability to empathise with those whose backgrounds diverge from our own has never been more vital. Tourism, as the largest conduit for human movement, with a projected 1.5 billion international arrivals in 2024, holds the potential to foster cross-cultural understanding on an unparalleled scale.

The New Tourist

McClanahan envisions a new breed of tourist, one who embraces their role as a global citizen and cultural ambassador. “Imagine if each of those 1.5 billion people saw themselves as a citizen, a diplomat who's going out into the world”, she muses, “someone who is an ambassador for their country and comes looking to make authentic human connections with people who live in the place, not to just consume and tick a box”. How powerful would that be?

This, she believes, is the essence of the new tourist—an individual who approaches travel with humility, curiosity, and a genuine desire to engage with the communities they visit. In doing so, they may return home with a newfound perspective on their own culture and a deeper appreciation for the shared humanity that binds us all.

Not only that, but the new tourist can become the foundation of a less polarised, divisive world.

As someone who has visited almost half of the world's countries, immersing myself in the local cultures, I have always struggled to understand divisions. I have seen enough to believe that borders exist only in our minds.

That's why I felt I could relate so much with the original article and the book (which I immediately pre-ordered) and why I needed to write here.

Conclusion

As we navigate the complexities of the effects of tourism in an era marked by climate change, overtourism, and social media saturation, it's clear that a fundamental shift in our collective mindset is necessary. By embracing our identities as tourists, we acknowledge our individual and collective responsibility to shape the impact of travel on the world around us.

Through intentional engagement, education, and cultural exchange, we have the power to harness tourism as a force for good—one that bridges divides, fosters empathy, and equips us with the understanding necessary to confront the global challenges that lie ahead.

In Paige McClanahan's words, this is what gives her hope. Perhaps, as we embark on our own journeys with a renewed sense of purpose, this is what can give us all hope for a more connected, compassionate world.